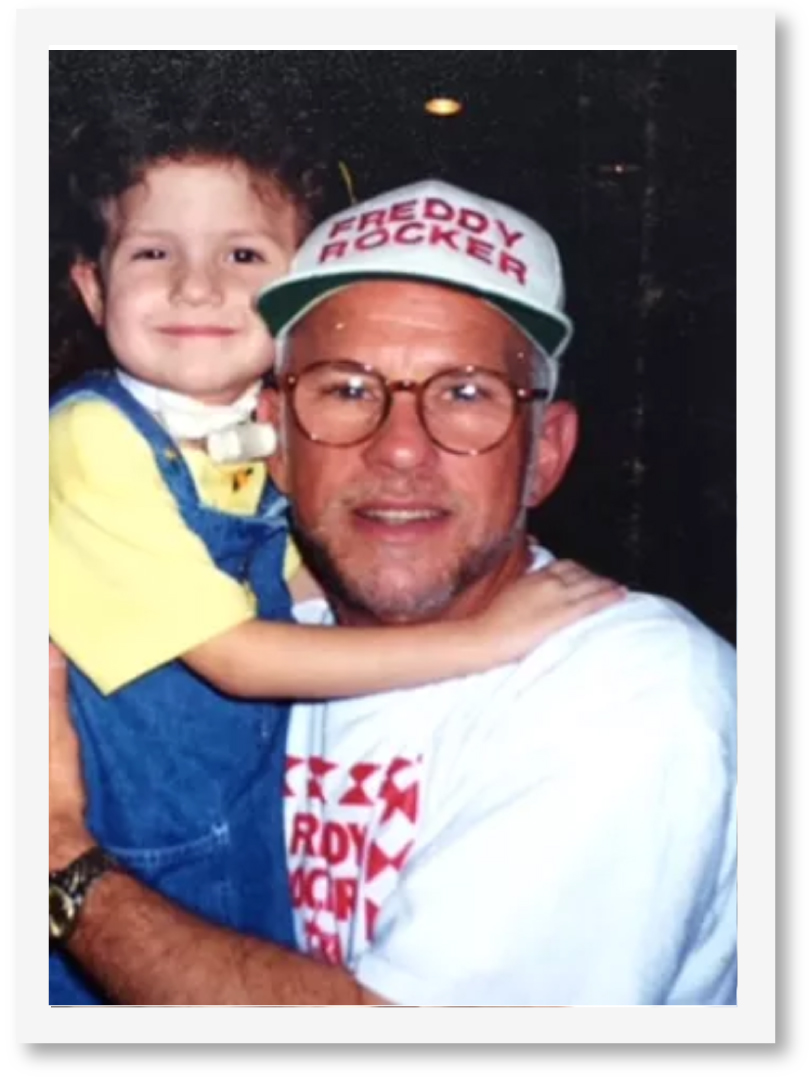

When I walk through the glass doors of Children’s Hospital in Boston, one of the most important pediatric medical centers in the United States, I am like Clark Kent jumping into a telephone booth. I make a dramatic change of persona, from Fred Feldmesser, gem dealer and private jeweler, to Freddy Rocker, uninhibited Mythical Rock Man. I leave the world of commerce and enter the world of the heart. I go from the world where everything has a price to the world where only one value exists, the life of a child.

On the mezzanine level of the hospital is a large open area with a performance stage. This is the children’s theatre, officially called the “Patient Entertainment Center.” Volunteers, some world-famous and some unknown except to those who spend their days and nights in this hospital, come here to entertain the children: magicians, folk singers, and storytellers. Freddy Rocker first appeared in the hospital almost forty years ago.

I arrive at the hospital about 5:15 p.m., stopping first at the volunteer office, where I check in with the staff and pick up all my materials. I put on my Freddy Rocker Gem Show tee shirt and a baseball cap with a red Freddy Rocker logo. The show is scheduled for 6:30. When I am “suited up,” volunteers help me transport all of the props and gifts, including 100 helium-filled Freddy Rocker Gem Show balloons, to the children’s theatre. We create a spectacle moving through the hospital corridors with all of these balloons.

At approximately 6 p.m. the audience members begin arriving. Nurses, volunteers, grandparents, parents, brothers, sisters, and the patients themselves in pajamas and bathrobes fill the room, perhaps fifty or sixty people in all. Forgetting where I am for a moment, I think that I have been plunked down into the middle of a children’s slumber party. As I look around the room, though, and see the bandages, intravenous feeding tubes, and wheelchairs, I am quickly brought back to the reality of time and place.

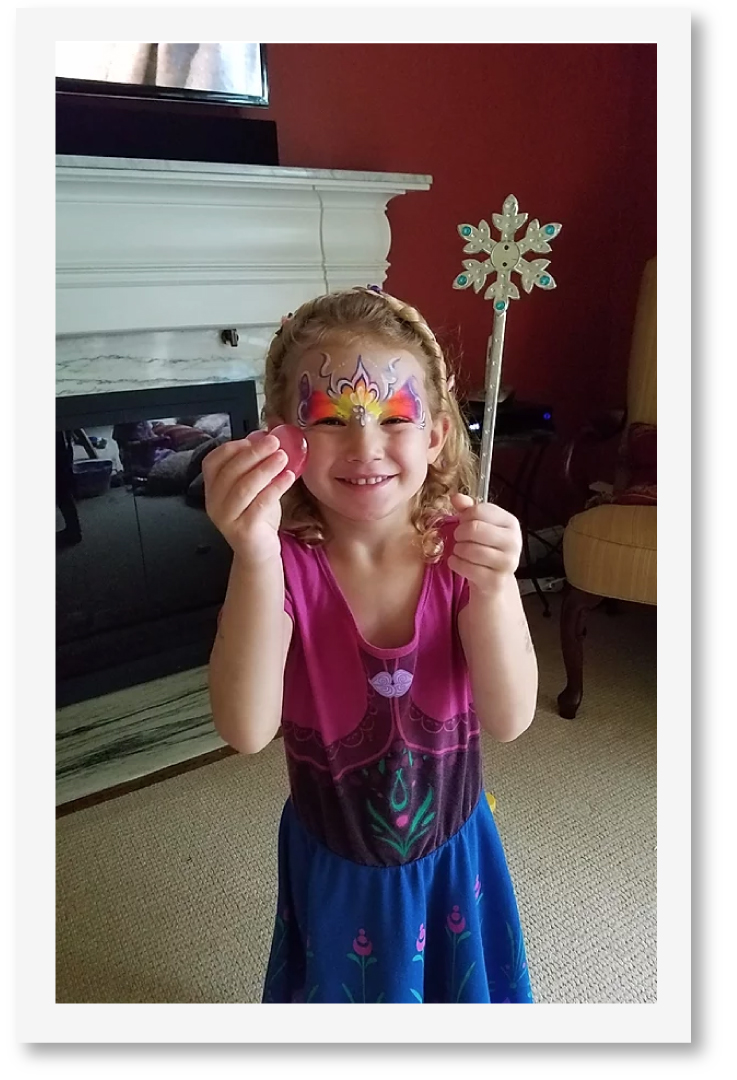

At approximately 6:30 p.m. the Freddy Rocker Gem Show officially begins. Each child has been given his or her very own Freddy Rocker Gem Show tee shirt, a baseball hat, two balloons, and a stuffed animal. I introduce myself and then suddenly shout out, “Who likes surprises?” capturing everyone’s attention. A few weak replies come back. “I guess you don’t like surprises,” I say with fake resignation. A few children protest. “Okay, I’ll try again and this time I really want to hear you. “How many kids really, really like surprises?” This time I am answered by a roar of voices all screaming “Me!” I promise all of the kids that a special surprise, a real treasure, will be given to each of them at the end of the show.

These children live in an environment where they need to follow precise rules and regulations. I am trying to give them a sense of freedom, even in the hospital setting. I want them to return as best as they can to being a child, at least for the next hour.

I ask, “Who knows Superman and Superwoman?” A few children raise their hands. Then, I take a funny looking, painted green rock from the table behind me and hold it up for everyone to see. “Who knows what this is?” A few voices yell back, “kryptonite!” They have been to other Freddy Rocker shows and are proud to have the correct answer.

“That’s right, kryptonite,” I say, pointing to the child who gave the answer. “Good, David.” I turn to the audience and ask, “What happens if you touch this piece of kryptonite?” Some kids answer that you lose your power or you faint. Sometimes, one will say, “you can die.”

The first time this happened I was shocked. These children do not need kryptonite to tell them about the peril of death. “No,” I say, “if you are a Superboy or Supergirl in disguise and you touch kryptonite, your ears will turn green and we have to call the doctors.” “You’re just joking Freddy,” a boy in the second row says to me. I address the answer to everyone. “No I’m not. Would I lie to a kid in a hospital?” I say with a twinkle in my eye. I watch as they waver between belief and disbelief, that magical ability of a child to accept either with his or her whole being.

I want the children to be as involved as possible. I call several kids up to the front and ask each to tell me his or her name. They all get a round of applause. I make them my special assistants and ask them to take the kryptonite around the room. The children who volunteer love the attention. It acknowledges their uniqueness and humanness, their value as individuals. When children become profoundly ill they often take on a terrible burden of guilt, among other negative feelings. Their identities become shattered along with their bodies, and they blame themselves for their families’ worries. I am saying, “You are wonderful and extraordinary.”

The show continues. I ask the kids, “What is the biggest number you know?” Some say one hundred or one thousand, or someone will yell out “infinity” or “google.” I then take a blackened rock the size of my fist from the table and hold it up for everyone to see. I ask them, “What is this and where does it come from?” I give them a hint and tell them that this rock does not come from the earth. After some wild guesses by the children, a parent or grandparent will stand up proudly and say that it is a meteorite. I tell the kids the answer is correct and that the meteorite comes from outer space, is over two billion years old, and is probably the oldest object they will ever touch in their whole lives. They are amazed by this wonderful rock and delighted when I ask for a volunteer to take it around the room.

As the meteorite is circulating, I joke with the kids and their parents and grandparents. I ask different people how old they are. Kids will say they are three or six or eight and then I play with the older people. A mother will say she is thirty five, and I will act surprised and yell out, “Oh my God, that old?” The children laugh. Then, I tell them my age. Many times I am the oldest person in the room.

I turn back to the group and ask the kids, “How many of you have pets at home?” Most kids raise their hands and are eager to share the names of their pets, which include dogs, cats, hamsters, fish, and even ferrets and ants. I then hold up a huge, petrified tooth from a prehistoric Great White Shark. I ask, “How many kids have pet sharks at home?” The children stare at me in disbelief. I ask them how big they think this shark was when it was alive. Their answers range from six inches to one hundred feet. I ask for two volunteers and give them a thirty-foot length of rope. As they follow my instructions to stretch the rope out to its full length, I tell a sea of apprehensive but amused faces that this is how long the shark was when it swam in ancient oceans.

The next part of the show is always the most fun for the children. “What are your favorite foods?” I ask, looking around the room. The children respond with the sweetest answers, “Spaghetti-Os, hot dogs, ice cream.” Every so often a child will say “filet mignon,” or “lobster.” I ask the grandparents and the parents also, and their answers are always as interesting and revealing as the children’s.

Then I say, “How many kids like eggs?” A few raise their hands, and I announce that I have a very a special hard-boiled egg for them. I bring up a volunteer, a little girl, and introduce her to a round of applause. “Here, take a bite,” I tell her, offering an egg-shaped piece of agate. Of course she cannot bite into it. Now I say, “Let’s try to break it.” The little girl holds the egg up and drops it. It bounces slightly but does not break. She laughs, and, with a sense of relief, returns to her seat.

I point to a large map of the world and show them Brazil, where the agate egg originated. I tell them that sometimes what looks real is not real. I tell them about all kinds of objects that can be carved from different kinds of stones.

At this point I ask for volunteers, who come up to the stage and form a circle around a ten-foot-square piece of plastic. Children in wheelchairs use a ramp leading up to the stage. The excitement builds; the children do not know what to expect. I give each child two real eggs and ask, “How many want to make a mess?” They yell out, “me! I do!” “Okay,” I say. “On the count of three you can throw the eggs as hard as you can into the center of the plastic.” I step back and scream out, “One, two three!” Eggs go flying all over the place. The scene is the funniest and sweetest I have ever witnessed.

The children are hysterical with laughter. Everybody is applauding and smiling. The children have deliberately made a giant mess. It is just what they needed. It is just what Freddy Rocker wanted. Hospitals have strict rules, generally for important reasons, and one of the cardinal rules is that you should not intentionally make messes. Freddy Rocker is saying, “Kids, it is okay and fun to make a mess here, with me.” I am allowing them to become children again and do what all children do.

The next part of the show involves real gemstones: diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires. Much to the surprise of the parents and hospital staff, I let the children touch and hold these valuable stones. I explain how they are found in the earth and cut to reflect the light so that they will sparkle. What I am really telling them with these objects, games, and stories is that the world waits for them outside of the hospital, a world filled with magic and color and excitement. I know that some of the kids will not have the opportunity to experience this world. However, I also know that hope is a wonderful and essential part of a child’s life, and that these gems help give a dimension of hope to them.

I ask for two volunteers to come up to the stage and get Freddy Rocker Crown Coloring Books, Freddy Rocker Jewelry Coloring Books, and crayons to pass out to the children in the audience. The Crown coloring book contains an adjustable cardboard crown that each child can wear. It also contains sheets of paper with the different shapes of gemstones, which the children can color and attach to their own, individual crowns.

The Jewelry coloring book has pictures of rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and diamond, and brief descriptions of each stone. The last two pages contain “fun facts about gemstones.” All children love to color and the children in the audience are no exception. The children are learning about nature and they take to their projects with seriousness and abandon. Freddy Rocker is there to share the magic and beauty of gemstones with them.

I move around the room as the children color and talk to them about the stones and their pictures. Really, though, I am talking to the children about themselves. I do not hide from their sickness. I ask about their illness and their surgeries. I try to be soothing to both the children and their families, and I do whatever I have to in order to make a child laugh.

After I have spoken to each of the children, I return to center stage. Nearly an hour has elapsed and the Freddy Rocker Gem Show is coming to an end. Some kids try to give back the coloring books. So much is taken away from them during a profound illness, mostly their childhood. I tell them that all of the gifts tonight are theirs to keep. They are still children, and they still thrill to be able to keep the smallest treasure. Here in the theatre for these precious minutes their childhood is returned to them through laughter and these simple gifts.

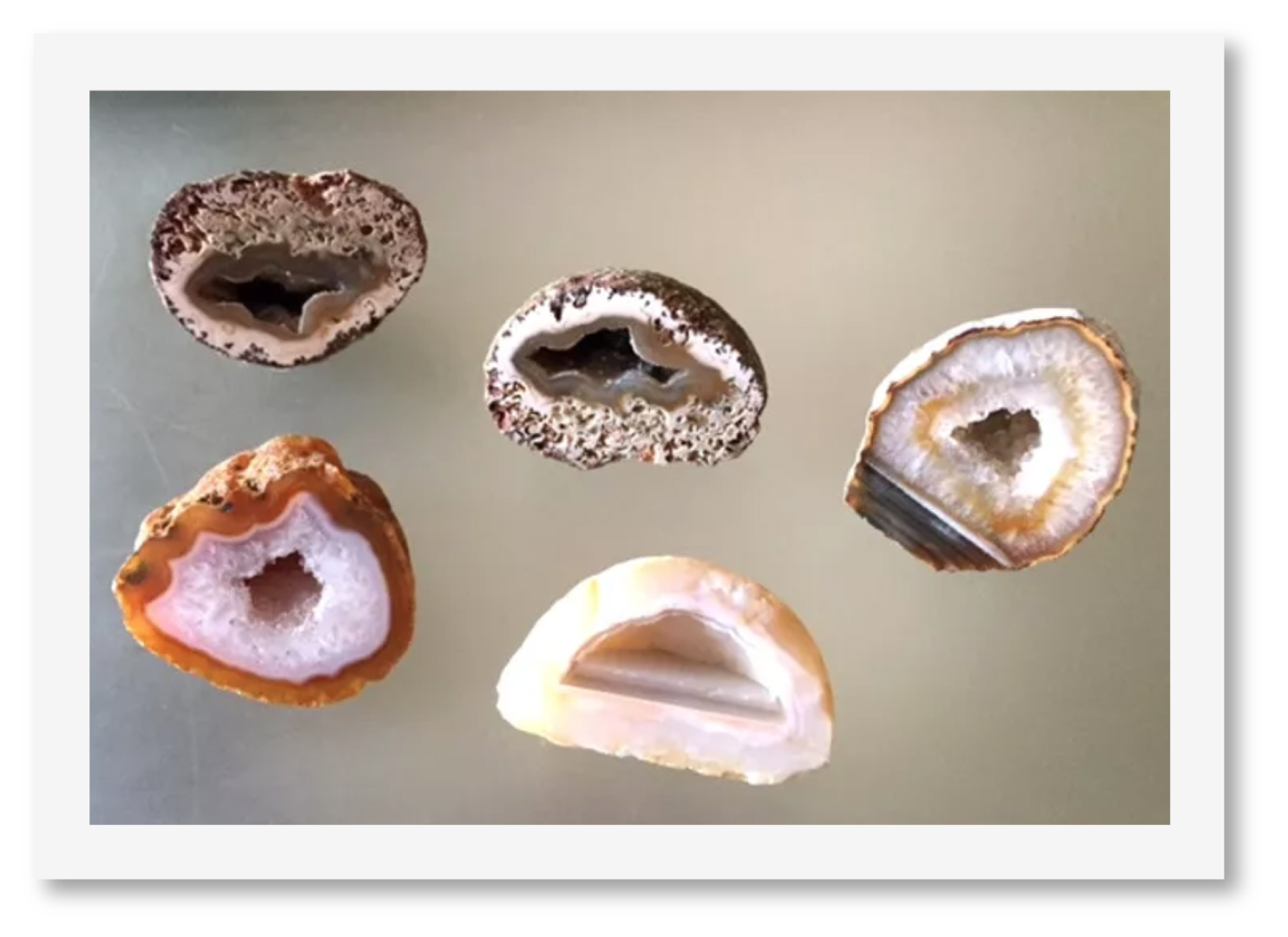

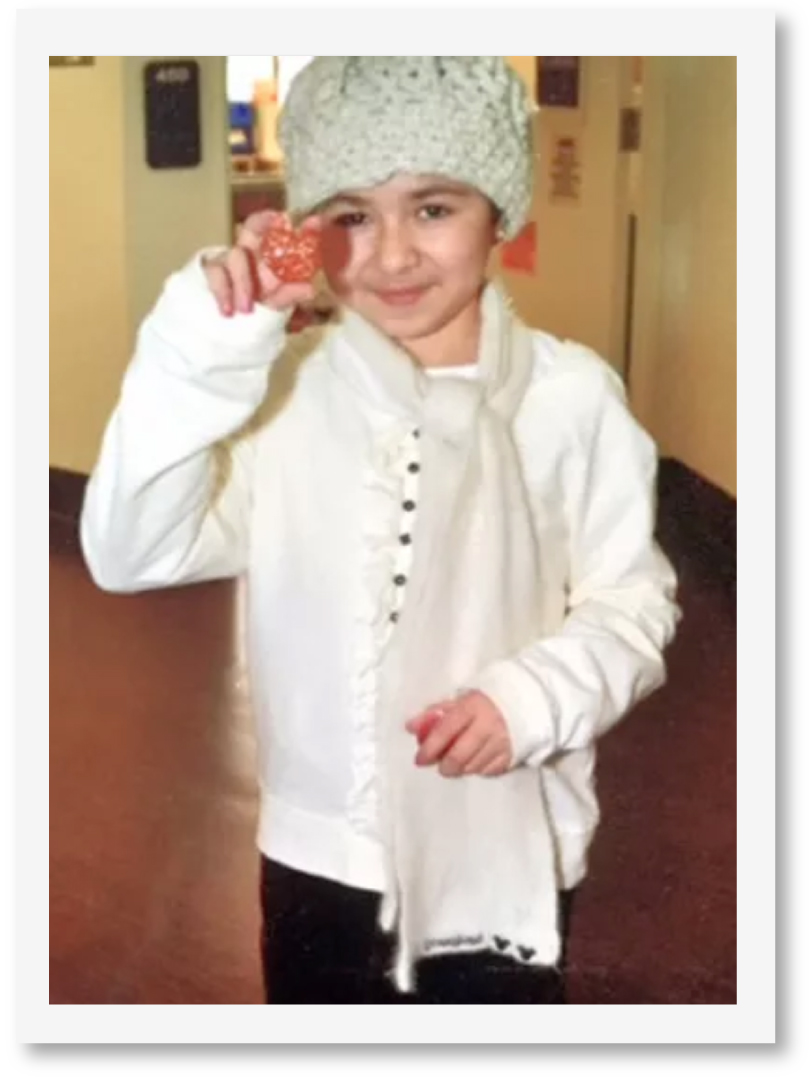

I ask for quiet and remind them of the surprise I promised at the beginning of the show. I walk back to the table and open a large rectangular box and hold it up for everyone to see. It is filled with individual boxes of jewel-like agate geodes from Brazil. Screams of delight and disbelief fill the room. I tell them that Freddy Rocker keeps his promises and that I have one treasure for each child. I tell them that the gems in the box are called agate geodes and have come from deep in the earth. Each child, I announce, may choose his or her own treasure.

All eyes follow me as I move from child to child, patiently waiting while each carefully ponders which of these beauties to choose. Little girls, being typical girls, choose slowly and carefully, boys usually very quickly. Some children decide to swap geodes with each other. They just are being kids.

When everyone has selected a geode, I announce to the children that I want to make a deal with them. When they get better and leave the hospital and go back to school, I want them to wear their Freddy Rocker Gem Show tee shirts and bring their agate geodes for “Show and Tell.” I want them to let their friends and classmates know that other things go on in hospitals beside “medical stuff.” I tell them that they are now and forever official members of the Freddy Rocker Gem Club.

We say goodbye to each other and the show is over. Children drift off with their parents and nurses, weighted down with their balloons, stuffed animals, coloring books, tee shirts, baseball hats, and agate geodes. A little boy of seven has stayed behind. He is recovering from open-heart surgery. “Mr. Rocker,” he asks plaintively, “can I have a geode for my sister?” I open the box and let him choose another geode. He makes his decision and then takes me around the leg, hugging tightly. “Thank you Mr. Rocker.” The children, parents, grandparents, and volunteers are gone. Freddy Rocker says goodbye to a remaining nurse and, once again back in his Clark Kent guise, steps out into the Boston night.

Fred Feldmesser